Tomorrow’s Soon Yesterday – But Today Is Still Today

Indoor Horizons 3 – Imprinting the idea in wax. The tabula rasa of the mindful eye.

The first Diorama opened in Paris in 1822, breaking the fourth wall to experience a new landscape within.

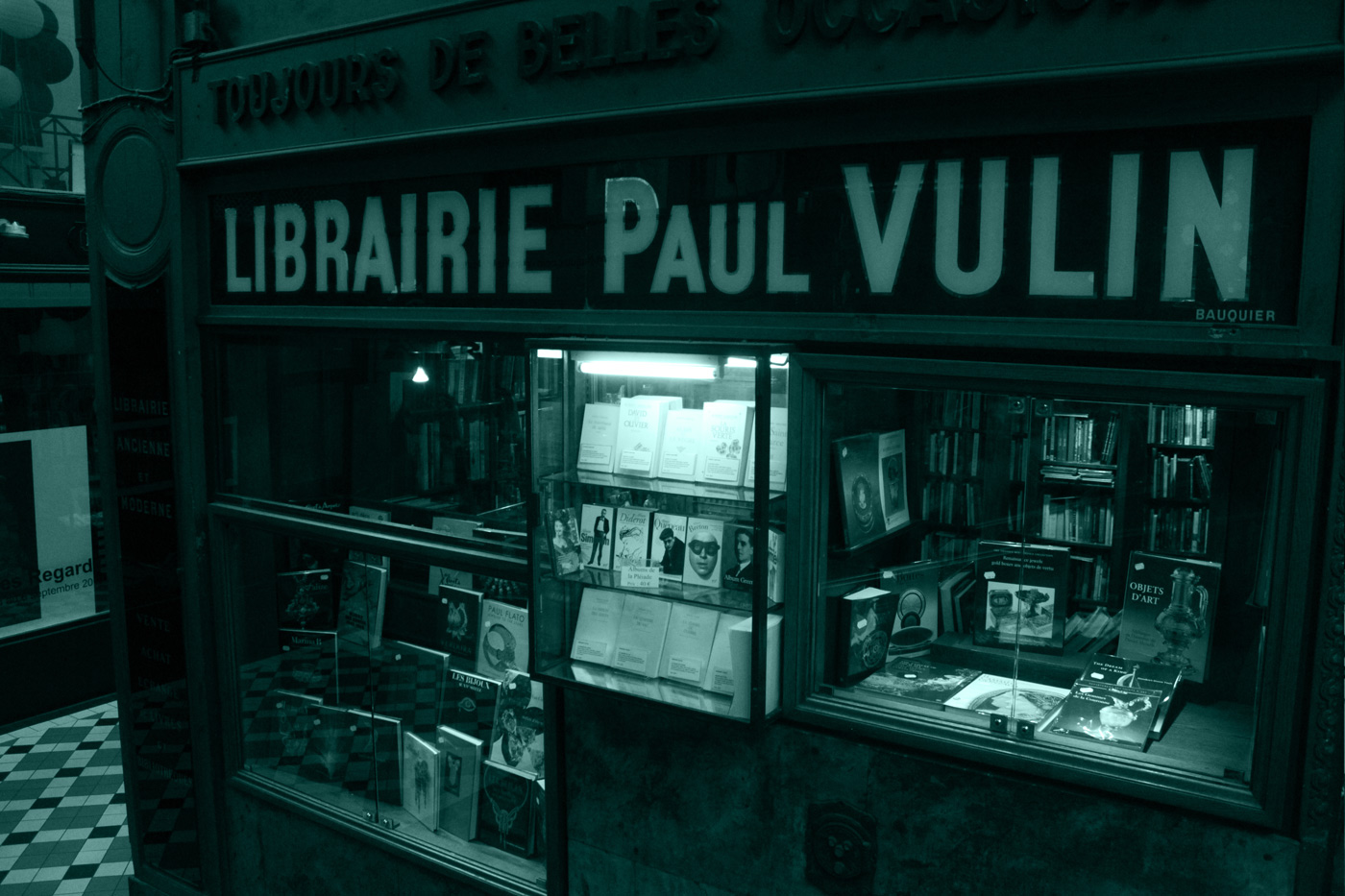

Leaving Walter Benjamin hovering over his blank page at a cafe in the arcade, let us continue our Indoor Horizons journey (navigating once again the dangerous terrain of the creative imagination without waiting around any longer in the vain hope that Virgil might turn up to be our guide), as we rise the ten steps to investigate the second stretch of the first heated Arcade in Paris – Passage Jouffroy – which will take us south in the direction of the Seine towards Boulevard Montmartre. Facing us is the amazing Musée Grévin, a waxwork museum founded in 1882 by the journalist Arthur Meyer, named in honour of the creative director Alfred Grévin. When given a blank slate he created a world in miniature, a fantastic vision of an imagination inhabited by wax caricatures. Emile Zola was a frequent visitor to Alfred’s world and the arcade was a place to which many writers turned to escape the main streets, returning to seek inspiration in the weird and wonderful objects in the windows hoping they might spark a new idea with which to graffiti the blank page.

The blank slate is a common challenge to the thinker, the writer, the photographer, the artist, the teacher, the dancer, the architect, the scientist, the architect, the athlete, the contemplator, the puzzle solver, the composer and the metaphysician. How do we face the abyss of the blank slate? How do we apprehend the transcendent flash of that creative spark and place it on paper? How do we make concrete the essence of something half glimpsed in a whisp of vapour, in the scent inhaled in a doorway, in the sound of the river merging with the hush of traffic. How do we penetrate that fog and bring something permanent back from the other side, as William Blake did return with gold from his visionary realm to imagine his own green and pleasant land?

We noted that Coleridge’s pleasure dome collapsed before he fully captured the complete vision of Kubla Khan. For Walter Benjamin he looked to the journey taken by Baudelaire and Breton through the dioramas of the arcades of Paris to recreate from the fragments the world they fashioned with words. The Diorama, the world in miniature can still be seen in Passage Jouffroy, represented by the glass snow globes and dolls houses which decorate the shop windows, all situated inside their own glass house of the iron framed arcade, living proof that ideas can be captured, from regions often considered beyond our grasp, to construct a world of imagination, where ideas are given shape and planted firmly in the realm of the everyday.

Andre Breton mentions Passage Jouffroy in his surrealist novel Soluble Fish. Here he used an innovative future perfect to portray the poetry of his dreams, like Coleridge he sought to build a vision to echo the world he experienced in those transcendent moments but the characters returned from the other side and followed him into the physical world of Passage Jouffroy; the arcade packed with curious characters in the window of the waxworks, the phantasmogoria which so enthrallled Baudelaire still haunt the windows fronting onto the arcade. The Dandy is alive an well in Passage Jouffroy. The ghost of the cane can be caught on reflection when the mindful eye takes the time to stop and look.

Stop and look- a simple instruction at the behest of John Ruskin. Perhaps take one painting or sculpture in a gallery and look at that, don’t try too hard, just observe it for longer than a minute and see what happens. In a new city with limited time there is a temptation to seek the impossible, to bring back an authentic feel of what that city and it’s culture has to offer. On arrival, everything is a new chance to grab life, yet the eye sees multiple colours screaming for attention, buildings are just shapes, the landscape is an unchartered wilderness which must be conquered by the senses for fear of wasting the chance to return somehow uniquely enriched by the ecstatic truth of the place itself.

Rather than racing past a million moments in a bold attempt to experience their authentic presence (perhaps a guide book suggests an expedition through an exhibition to try and capture at speed a tiny essence of the original moment of apprehension) – stop. Look and look again, notice and notice what you notice. Somewhere in the blur of brickwork reflected on your sunglasses there is a city waiting to impress itself upon you. There is a fine art you need to master, the art of seeing without looking too hard, stumbling upon a fresh perspective using what Gaston Bachelard called your active imagination, whilst being open to the drifting possibilities of chance encounters, impressions which might only rise to the surface in the weeks or years ahead. It is hard to submit to the experience whilst actively seeking to see the world in a fresh and open way, being actively passive, awakening the active imagination, watching for the ripple before throwing the pebble, but it is in the mastery of such a creative process that a moment can explode and go on exploding for the rest of your creative life, setting fire to scraps of paper to enlighten unexpected moments, in cities far away, forever reawakening the sense of place which appeared to you because, for once, you were truly open to let it land on your blank page.

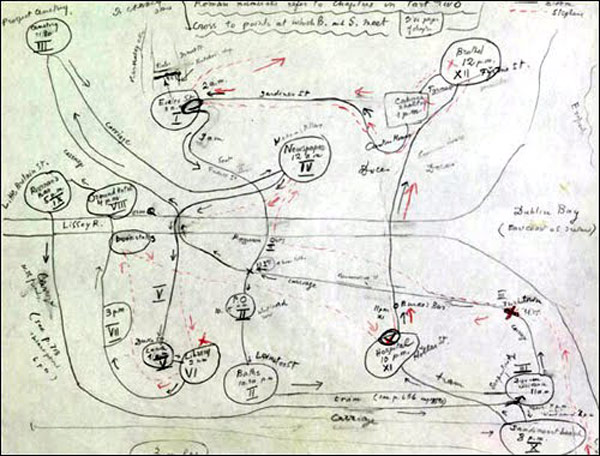

When Joyce brought us back to Howth Castle and Environs at the start of Finnegans Wake, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, was he simultaneously confronting his blank page in Trieste, in Zurich, in Paris and back on the deck of the boat leaving Dublin? (Drifting over the spot where Vladimir Nabokov has written Dublin Bay on his sketch above, about to exit page right) – Back on the deck with his character Stephen at the end of his portrait of the artist as a young man, going to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience, looking south (towards the Martello tower at the start of the journey in Ulysses) before craning his neck to the north (Howthward ho – towards the end of Ulysses – and towards both the start and end of Finnegans Wake) letting that moment impress itself on his soul, as yet unaware of how the essence of that very instant would one day bring his whole creative journey full circle, both inside and outside of time, forever shaping the lopsided view which would change the way the world looked upon the printed page. On that slow drift into exile, the slow drift from A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man, through Ulysses into Finnegans Wake was he ever mindful of that moment or would he have described his state of being as mindlessful?

Try this different approach, let your being become mindlessful, let the riverrun like the wake of Finnegan. Allow a moment for the place to gain a sense of space and offer a new perspective upon those reflective shades. Rather than grabbing at the air try and let the place flow through you. This is the old Zen concept of listening to a mountain rather than trying to climb it at speed to reach the top only to look at somewhere else, darting the eye around the horizon looking for the next summit to conquer whilst missing the experience of where you actually are. Instead of trying to conquer a place or it’s vast array of culture, try Ruskin’s stop and look. Sketch a statue in a notebook for five minutes and let everyone else wander, you can catch them up. It need not even be a sculpture or a painting – a gallery is there to awaken the eye to the shapes of the world. That might be the silhouettes of people on the escalator at the Louvre, cut out shapes against the glass pleasure dome, like Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, we can grasp the essence of the pure moment with the mindful eye.

The return of that essence comes through those who have looked at the abyss and taken the leap. John Ruskin getting us to stop and look, Proust describing the transcendent moment he read Ruskin, Baudelaire writing about Proust which was revisited by Benjamin in his vast Arcades Project, Susan Sontag writing about Benjamin in her study of the moment when the eye frames an image before the click of the camera lens, Gaston Bachelard investigating the poetics of space using active imagination; they were all brave enough to take on the abyss, to step into the dark and start that journey which made a connection to the past and to the future by experiencing the present. If you want to write a reminder in your notebook when you are going to visit somewhere new try the heading – Tomorrow’s soon yesterday but today is still today.

Stepping out onto the Boulevard Montmartre where Jean Seberg met Nico to head towards the Passage Des Panoramas, it is a short walk west to Proust’s cork lined room where the Boulevard Montmartre becomes Boulevard Haussmann, and where J.K. Huysmans placed a character in his novel, À rebours (Against The Grain or Against Nature), the yellow book mentioned in the trial of Oscar Wilde and Dorian Gray. Having captured the indoor horizon of the diorama we must take that with us to enhance the panorama, the oldest covered passageway in Paris.